When I was a kid I delivered the North Staffordshire Evening Sentinel for a couple of years. Or to put it another way: I had a paper round. There were two compelling local football stories during my time and one compelling national story which became local – the kidnapped heiress Lesley Whittle was found hanged down a mineshaft on rough parkland a few miles from where we lived. Each of the football stories revolved around individuals rather than matches. Both of them slowed me to a dawdle and then to a dead stop as I sat on a wall absorbing the details before I got on with my work. My reading speed was, and remains, remedial; the Evening Sentinel often ‘came late’ in my day. To compound matters, back then the Sentinel was a broadsheet with the typeface set at such a small point size and so tightly compressed (into what we would now call single line spacing) that it was no wonder so many of the ancients kept a magnifying glass on the sideboard: I used to think it was just because they were old and decrepit; now that I need to wear several different prescriptions of spectacle myself (according to activity: one pair for the computer, one pair for reading, another for driving), my view has changed.

When the first story broke it made it to the main television news bulletins and was front page of the Sentinel for days. One Sunday morning in October ’72 Gordon Banks crashed his car on the way to his home in Loggerheads, on the road to Market Drayton, where my dad comes from. The crash put our goalkeeper in hospital, and the daily bulletins eventually conceded the grim fact of the matter – Banks had lost the sight in one of his eyes. I cried several times over those days and in this I was not alone. There were pictures of the player in his hospital bed on the local news surrounded by cards and flowers and teddy bears, but the focus of my attention was drawn to the sinister patch of wadding over the ruined right eye. Banks was so pre-eminent as a goalkeeper (not only England’s No 1, but by common consent the best in the world) that our then manager, Tony Waddington, still believed he could play professional football even with this devastating handicap. It was only after testing him out by popping shots at him from all angles on the pitch at the old Victoria Ground that Waddo accepted the situation as it really was – the loss of peripheral vision was the end for Banksy.

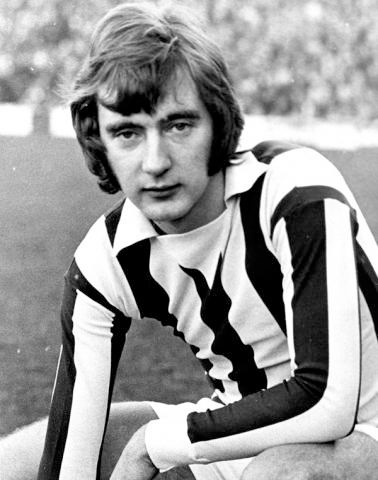

The second Sentinel story was much happier and concerned the acquisition of a new player. Stoke signed Alan Hudson from Chelsea in January ’74 for a club record £240,000. This would be like signing Cesc Fabregas for who-knows-how-much from Arsenal now. We were nicking a great player from a top London club; it was simply unheard of. Hudson was one of those gems who reputedly eschewed training unless it involved exercising his drinking arm. He was a fabulous flair player who could define a game on his own – see Calvin’s comment, 2nd below, for a vivid description of his technique. He had superb vision, and additionally, and most pertinently, he looked like he’d just stepped out of The Small Faces.

Like many with an association to the Kings Road (George Best spent half his life in a bar at the Sloane Square end) Hudson arrived with a reputation for being a dilettante and a playboy. As a consequence of this, and in common with flair players down the years (Rodney Marsh, Tony Curry, Glenn Hoddle, Matt Le Tissier) he was routinely overlooked by the England manager, who was at that point the dour pragmatist, Don Revie. My favourite Alan Hudson-playboy tale is the one that goes like this: eventually, after a large number of other players had withdrawn from the England squad through injury, Revie found himself in a position that left him with no alternative (that would not get him pilloried by the News of the World), so he telephoned Hudson on a Sunday afternoon to ask him to make his way to England HQ in readiness for a midweek fixture. Hudson replied that he would not be able to manage this as, ‘there was a party going on, and that it looked like it was going to go on for quite some time.’

Alan Hudson is the answer that most fans of my generation will give when asked to name the best player we’ve ever seen in the red and white stripes. This coming Sunday (October 11th) at The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, I’m going to be signing copies of my new book while Alan Hudson does likewise with his, and then I am going to be siting on a panel beside him answering questions. I think I’m going to be slightly nervous (but on the other hand, I don’t think many of the questions will be directed at me…)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.